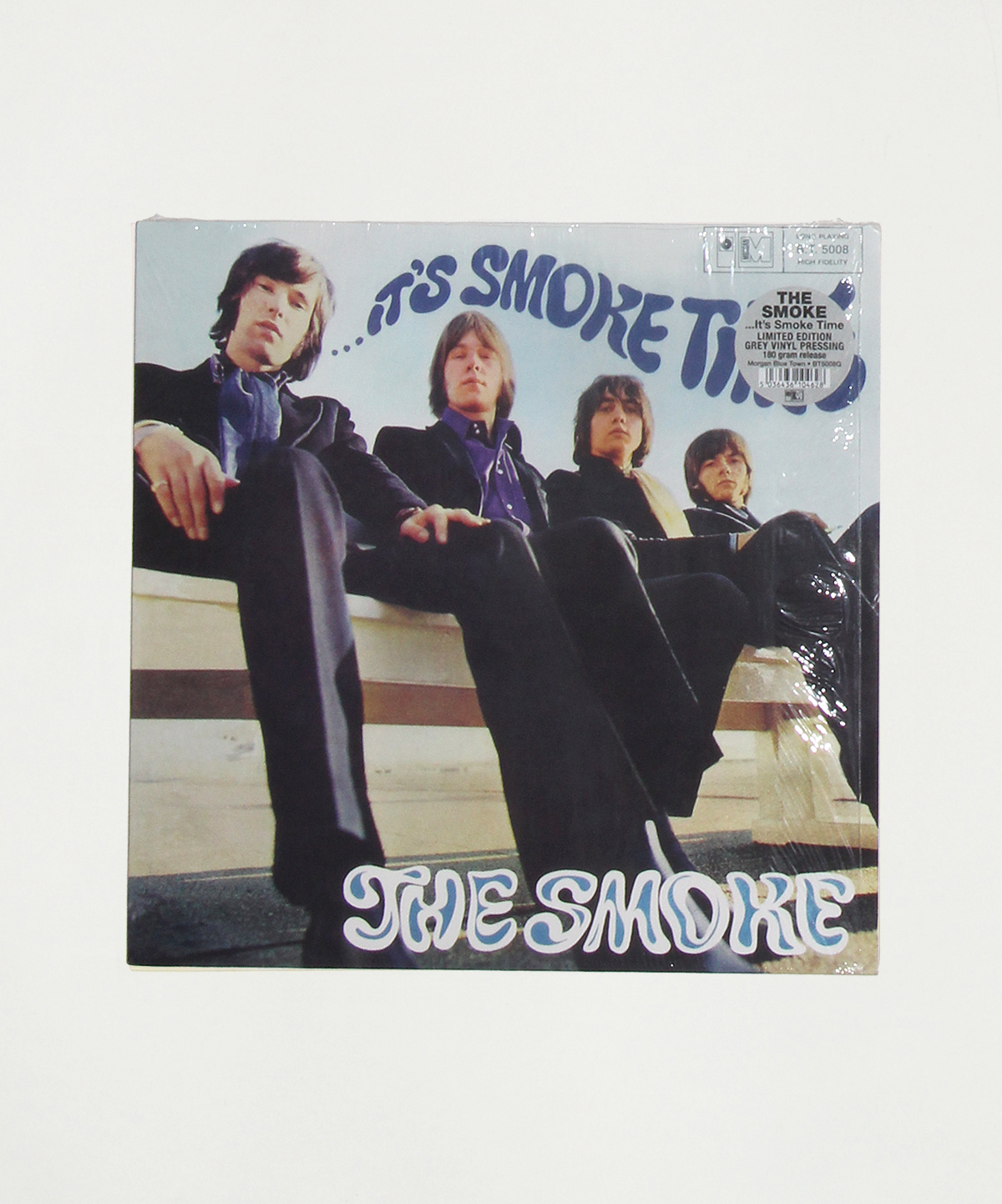

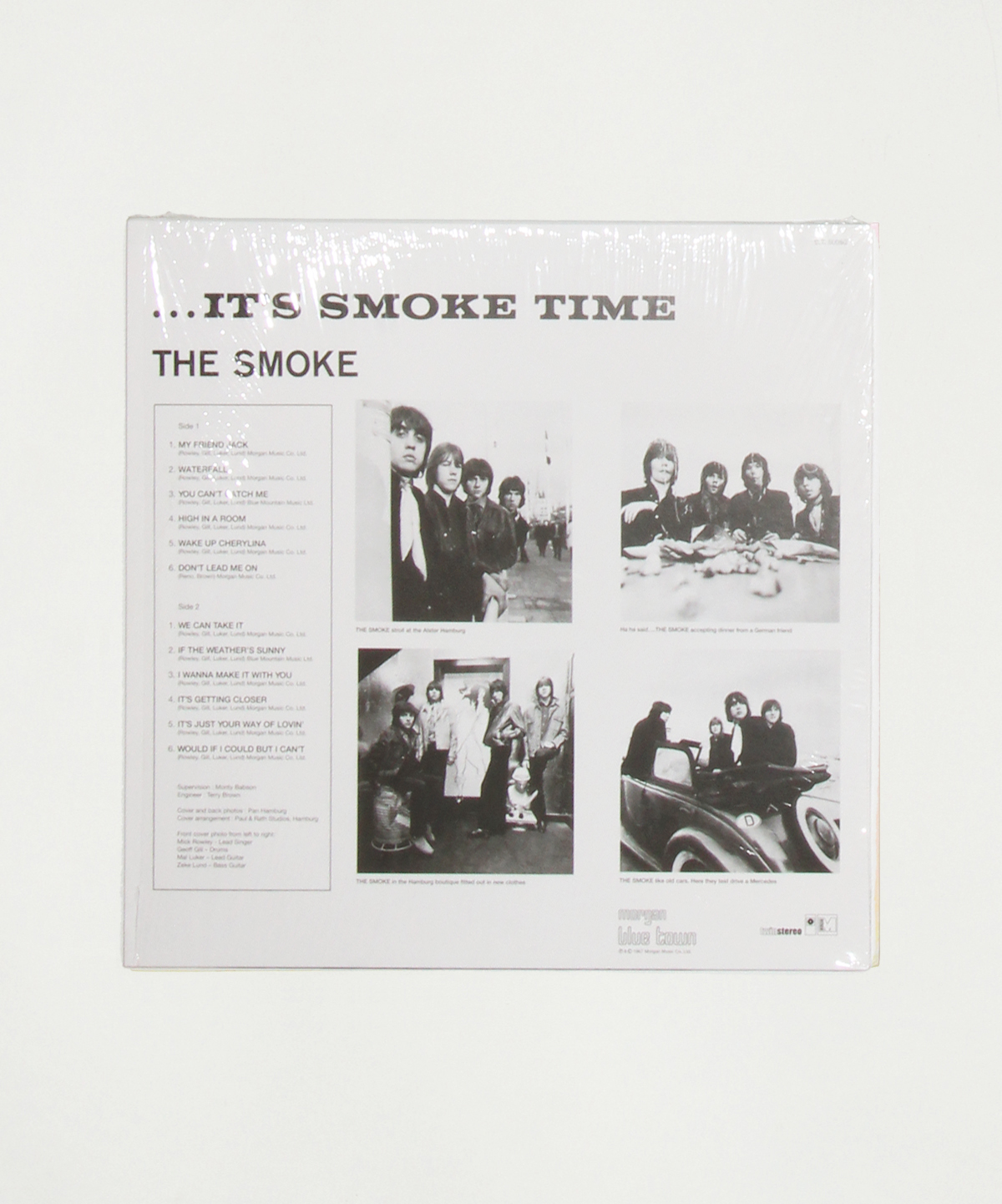

Media Condition: NM

Sleeve Condition: NM

Genre: Rock, Garage, Beat, Psychedelic

Notes: 2016 reissue pressed on white/gray 180g vinyl. Opened, but still in shrink.

If you like: Garage rockers The Action, The Easybeats, The Music Machine, or The Remains, you’ll thoroughly enjoy The Smoke.

About: More than any other band, the Smoke epitomized the groove of Swinging London–which was especially ironic when one considers that, at the height of their success, they sold more records in Europe than England. Their sound fell somewhere between mod and the Beatles–their instrumental attack was somewhat Who/Small Faces-like, yet they delighted in cheerful vocals and infectious harmonies and melodies. Only slightly popular on their home turf, and unknown in the US, their biggest success was in Germany (oddly enough, for such a British-sounding group). The band hailed from York, where bassist Zeke Lund and lead guitarist Mal Luker began playing together in a band called Tony Adams & the Viceroys, whose lineup eventually came to include drummer Geoff Gill. Though the band was successful locally, enjoying a decent fan base with a solid, basic rock & roll sound, built on early-‘60s songs, Lund, Luker, and Gill could hear the changes going on around them in music, with the rise of Merseybeat and the blues, R&B, and soul-based music coming out of London. They eventually decided to strike out on their own, playing a more ambitious repertory. They linked up late in 1964 with singer Mick Rowley and rhythm guitarist Phil Peacock, refugees from a band called the Moonshots. The resulting band, the Shots, played a hard brand of R&B, similar to what the Small Faces were doing–they were taken on as clients by Jack Segal and Alan Brush, a pair of London-based agents (Segal had the know-how, Brush the financing), who fronted them money for rehearsals and equipment, and got them signed up with independent producer and music publisher Monty Babson, who cut four sides with the group, two of which were issued as a single under license to EMI-Columbia. It was at just about that time that events began breaking against the band–they lost Phil Peacock, who wasn't comfortable with the more complex sounds the rest of the band were interested in generating, and they lost their financing. They gamely decided to carry on as a quartet, the single-guitar configuration lending itself to an edgier sound, and sought new backing.

That was how they ended up in a bizarre management situation, when they were offered a seeming rescue by a pair of twin London-based entrepreneurs, Ron and Reg Kray. Renowned today the world over as notorious gangsters, the Kray brothers have been immortalized in books, including Profession of Violence and Reg's own autobiography Born Fighter, and one feature film (The Krays), and were even memorably satirized in one Monty Python sketch (“The Piranha Brothers”). They were among the top crime kingpins in London at the time, and among their other enterprises, they had an interest in a few clubs, and thought at one point that a more direct participation in the entertainment business might prove lucrative. (And yes, it sounds funny to read it, or even to write it, but that is exactly how Morris Levy, an American gangster and club owner, came to go into the record and publishing business in New York, and ended up founding Roulette Records). Thus, they signed the group and became the Shots’ managers, but were never able to do anything with them in terms of bookings– strong-arming clubs for “protection” money was more their specialty than lining up engagements. The band decided to abandon the contract, and when they were served with an injunction, they were left unable to perform.

As luck would have it, however, they still had a publishing and recording contract with Babson and access to his studio, and so they took advantage of their ban on performing by writing and making records. Indeed, thanks to the fact that they were barred from performing as a band, the Shots probably had more free time to write and record than any working group in England (even The Beatles were touring in those days, though not for much longer). It was during this period that they also decided to change their name, dropping the Shots–no one remembered the Moonshots by this time, anyway–in favor of the Smoke. One of the songs they came up with was “My Friend Jack,” a mod-flavored psychedelic number authored by Rowley and Gill. With its march beat and mix of shimmering and crunchy reverb-laden guitar, it was a catchy, striking, aggressively trippy work–in America, it would've been called psychedelic punk–that now seems like the most delightfully subversive piece of freakbeat, somewhere midway between the Who’s power-chord-drenched teen anthems and the trippy cheerfulness of, say, “Dr. Robert” by The Beatles. Its drug references were so potent that the song had to be rewritten before EMI would touch it; released in February of 1967–a period in which “Penny Lane” and “Strawberry Fields Forever” were as challenging or ambitious as the label wanted to be–the single only made it to number 45 before being banned by the BBC, limiting it to three weeks on the U.K. charts. In Europe, however, the record soared; the group were also fortunate enough to appear on an installment of the German television show Beat Club, alongside Jimi Hendrix, The Who, and Cliff Bennett & the Rebel Rousers. “My Friend Jack” ended up riding the German pop charts to the top, and earned the Smoke a place on a tour with The Small Faces and the Beach Boys.

They were now stars, although not in the place they’d expected to be. The single charted high in Switzerland, France, and Austria as well, and suddenly there was demand for a Smoke LP in Germany. They delivered this in the form of It’s Smoke Time, comprised of the best of the year-old tracks recorded for Babson in the spring, summer, and fall of 1966. The band actually relocated to Germany, while continuing to release records in England–their recording contract was sold to Chris Blackwell in late 1967, and he soon took over their management as well; they were free of their obligations to the Krays by then (who had, in any case, been distracted by a gang war and a prosecution). They cut some fine psychedelia and crossed paths with the members of Traffic in the studio during this period. The end came out of a degree of weariness, after five years of work and perhaps the sincere belief that they’d already enjoyed most of the fruits of their brief pop stardom–they declined to obey a Blackwell summons to return to England for a recording session, and that marked the effective end of their history, at least as a classic British beat/freakbeat outfit.*Richie Unterberger & Bruce Eder

A favorite track: Don’t Lead Me On